The Day the PowerPoint Lost, and Culture Won

Strengthening conflict capability through visual storytelling and cultural alignment.

When I arrived in Alice Springs to work with Community Safety Patrol teams from several Central Desert communities, the purpose appeared straightforward. We were there to deliver introductory mediation and peacemaking training — structured content, clear steps, and practical tools intended to support frontline teams who regularly respond to conflict. The program was planned carefully, the slides were polished, and the learning pathway was mapped out. But almost immediately it became clear that while the content was sound, the delivery method was not aligned with how people in the room actually learned, engaged, or made sense of conflict. Within the first morning, it was obvious that culture, not PowerPoint, would be the real teacher.

The Purpose: Connecting Traditional Peacemaking With Formal Mediation

The Central Desert Regional Council had invested heavily in strengthening the capability of their Community Safety Patrol teams. These teams are often the first to hear about disputes, the first to respond to escalating tensions, and the first to step into situations where relationships, history, and family dynamics all intersect. The aim of the training was to introduce a structured approach to mediation that could complement the existing cultural practices already operating within each community. We wanted to provide a clear, repeatable process that would help teams feel more confident and consistent in the way they navigated conflict on a daily basis.

The Turning Point: A Drawing, a Comment, and a Shift in the Room

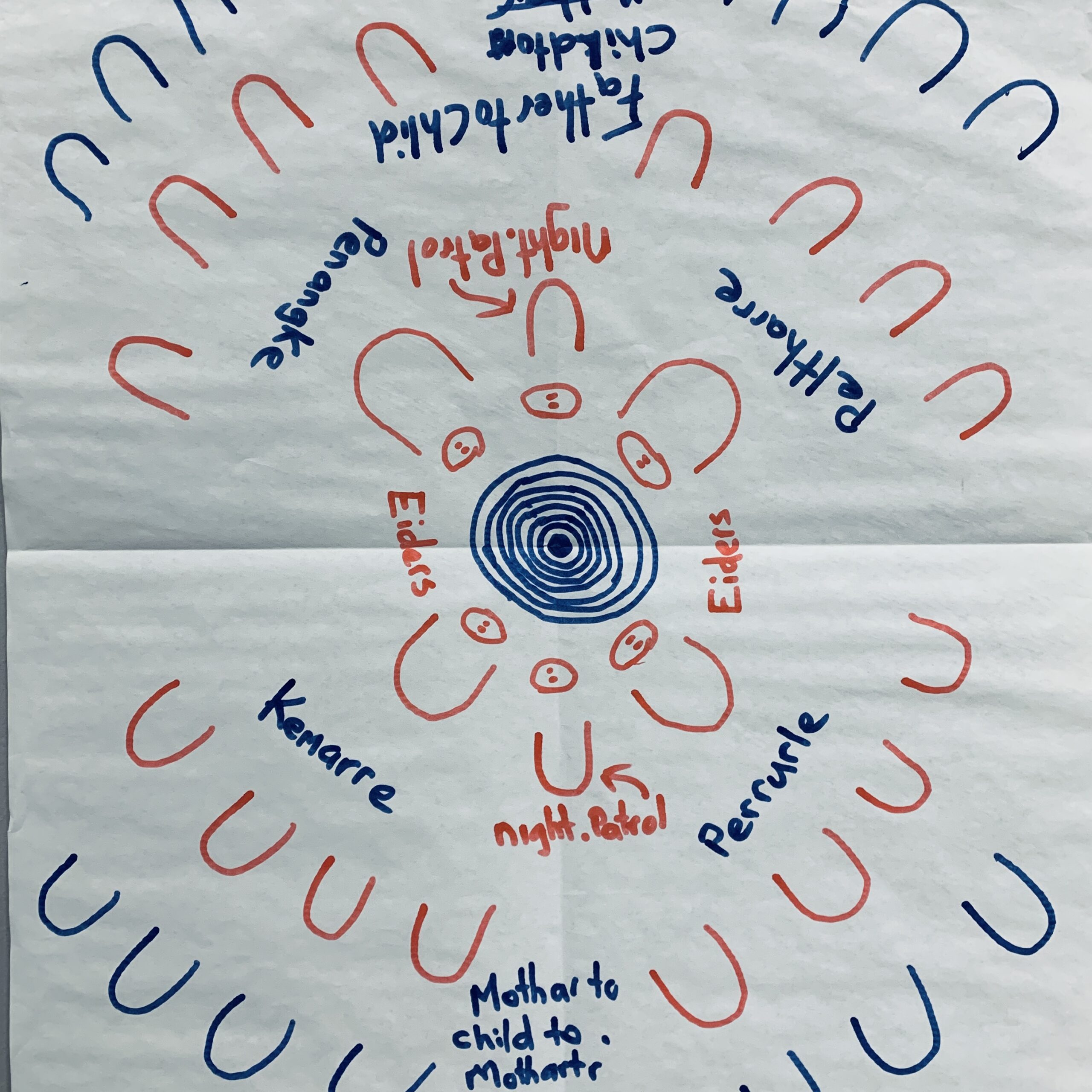

The moment everything changed came from two simple but powerful pieces of feedback. As I was explaining the formal steps of a Western mediation framework, Ronnie Hagan sat quietly at the side of the room sketching. When I paused to check in with him, he showed me his drawing: a traditional peacemaking meeting from his community. It captured who sits where, who speaks first, how people are brought into the circle, and the slow, relational pacing that sets the tone for resolution. It was mediation, expressed through a different cultural language.

Not long after, Stephen Briscoe looked up at the slides and commented, with complete honesty, that there were “too many words, mate.” The entire room laughed, and I did too — because he was right. The slides were tidy, but tidy does not mean useful. Those two moments revealed that the training would need to be re-centred around cultural logic, not imported structure. The program had to shift from a system-led approach to a community-led one.

What We Actually Did: Rebuilding the Training From the Ground Up

From that point forward, we set aside the slide deck and rebuilt the program using the community’s own knowledge and lived experience. Instead of lecturing, we laid large sheets of paper on the floor and mapped out how conflict is traditionally handled in each participating community. We explored who holds authority, who people turn to when things escalate, and the ways in which cultural leadership intersects with practical response. Western mediation steps were introduced only after traditional processes were drawn, discussed, and explained in detail. Teams began to construct their own visual frameworks — simple, clear diagrams that matched the reality of their work rather than the abstraction of a textbook model.

The training shifted from instruction to collaboration. It became less about teaching a system and more about recognising that the core elements of mediation were already embedded in cultural practice — listening, slowing down, separating issues, and helping people move from heat to clarity. The program was no longer something being delivered to them; it was something we were building together.

What Was Achieved: Confidence, Ownership, and Cultural Alignment

The change in approach produced real and meaningful outcomes. Participants began to see that Western mediation was not foreign or superior — it was simply another way of articulating practices they already understood. This recognition strengthened confidence. It validated the work they had always done, and it allowed them to connect cultural processes with structured tools without feeling they were abandoning or diluting anything important.

By the end of the training, teams had created shared language around their practice, developed diagrams that were culturally accurate, and gained a stronger sense of ownership over their own method of peacemaking. The program moved from compliance to relevance — and that shift made all the difference.

How This Shaped The Uncomfortable Company: Humility Over Performance, Culture Over Content

This project was delivered well before The Uncomfortable Company existed, but it heavily influenced its philosophy. The experience taught me that effective work in complex environments demands humility. People don’t respond to expertise performed at them; they respond to authenticity, shared humour, and the willingness to adapt when the room tells you that your plan doesn’t fit. It reinforced the belief that real capability building happens when cultural authority is recognised as equal to, or greater than, formal frameworks.

The Uncomfortable Company was shaped by this understanding. It was built on the principle that discomfort is not a sign of failure — it is a sign that something real is happening. If the slides need to be abandoned, we abandon them. If the process needs to be rewritten, we rewrite it. And if culture is the guide, we follow.

Looking Back: A Training Session That Became a Turning Point

When I look back on those three days in the Central Desert, I don’t think of the planned content or the set structure. I think of Ronnie’s drawing, Stephen’s honesty, and the way the room shifted from receiving information to creating its own practice. That shift was the real outcome. It reminded me that people learn best through their own stories, their own logic, and their own ways of seeing the world. That insight became one of the cornerstones of The Uncomfortable Company. The PowerPoint may have lost, but culture won — and from that, something far more authentic was built.